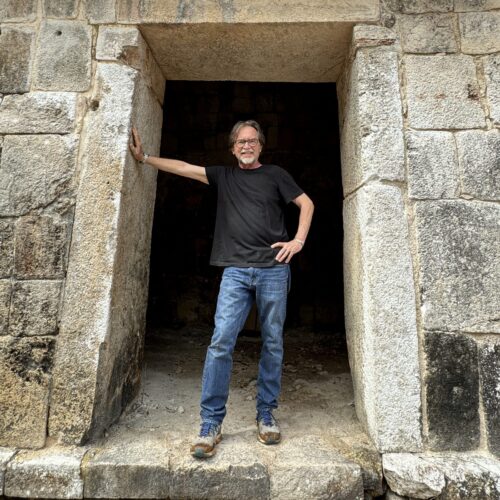

For decades, archaeologists like Dr. George Bey, professor of anthropology and director of the Millsaps Yucatán Program, relied on painstaking ground surveys to locate ancient Maya sites. “We would put a team together, march through the forest and if someone hit something we’d all run over, clear it off and map it,” Bey said. “Our first big survey, just one kilometer wide and twelve kilometers long, took twelve years.”

For decades, archaeologists like Dr. George Bey, professor of anthropology and director of the Millsaps Yucatán Program, relied on painstaking ground surveys to locate ancient Maya sites. “We would put a team together, march through the forest and if someone hit something we’d all run over, clear it off and map it,” Bey said. “Our first big survey, just one kilometer wide and twelve kilometers long, took twelve years.”

Today, that same work can be completed in a matter of months thanks to lidar, a laser mapping technology that stands for light detection and ranging. The revolutionary tool has completely reshaped how researchers approach archaeological sites and uncover history.

Peering Through the Jungle

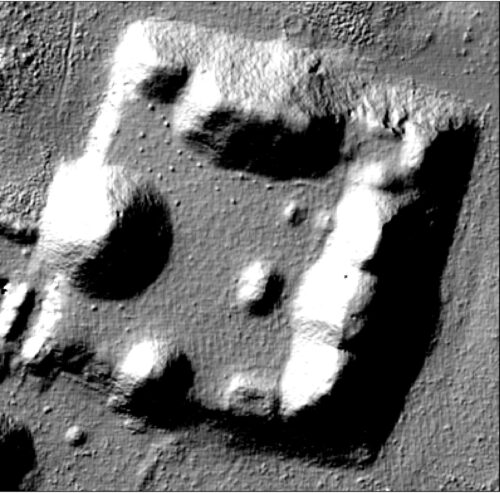

Lidar works by sending millions of laser beams from a plane or drone to the ground below. The imaging data is so vast and detailed that researchers can digitally strip away vegetation, revealing the contours of the soil beneath.

“Suddenly you’re looking at the surface as if all the jungle is gone,” Bey said. “We’re surveying gigantic areas of landscape and we can see not just a pyramid or a building, but smaller objects, like the openings of ancient cisterns.”

The level of detail is staggering. Millsaps’ first large-scale lidar survey covered roughly 460 square kilometers and revealed hundreds of previously unknown sites with thousands of structures. Using lidar has added a level of efficiency and precision that was previously impossible.

“For example, if you want to look for a Maya ball court, you look at the imaging data from lidar and pull out where they are and then just send your teams out to walk them and clear them off, rather than having to physically search,” said Bey.

“For example, if you want to look for a Maya ball court, you look at the imaging data from lidar and pull out where they are and then just send your teams out to walk them and clear them off, rather than having to physically search,” said Bey.

But this technology is a beginning, not an end. “Lidar finds things, but we still have to ‘ground truth’ them” he said, meaning researchers must visit a site to ensure it is what they think it is and date it.

Lidar imaging alone isn’t enough to draw conclusions about ancient Maya civilizations, like population density. That still requires the expertise and hard work of Millsaps professors, researchers and students with boots on the ground.

A Reserve with Global Reach

Millsaps’ Yucatán project is about much more than laser beams and digging.

Thirty-five years ago, Bey had an idea. “I wanted to find some place that nobody would bother us and we could work,” he said. It took about a decade of brainstorming and research, but around 2000, the stars began to align.

Thirty-five years ago, Bey had an idea. “I wanted to find some place that nobody would bother us and we could work,” he said. It took about a decade of brainstorming and research, but around 2000, the stars began to align.

From the beginning, this work has been rooted in partnership with the Mexican government, the National Institute of Anthropology and History, Cinvestav and the local Yucatán community.

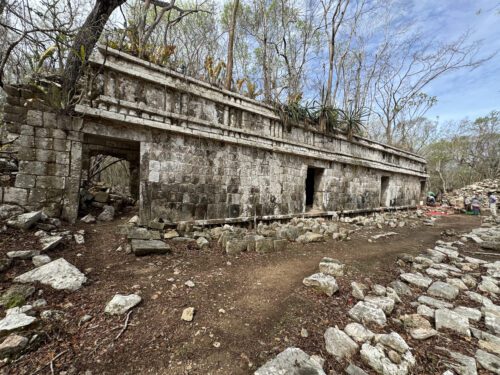

“Working with INAH archaeologist Tomas Gallareta, now the Millsaps Scholar of Maya studies we found 4,500 acres that was not only pristine, but was also for sale,” he said. “So Millsaps bought it, donated a piece to the Mexican government and developed an incredible, enduring strength of the college, something that is nationally distinctive and regionally unique.”

Bey’s dream came true. Twenty-five years later, continually working in partnership with Dr. Gallareta, Mexican archaeologists, local Maya communities and international scientists, Millsaps has built a flourishing research station that supports archaeological and biological conservation.

Today, the reserve is recognized in Mexico as a nonprofit dedicated to cultural and ecological stewardship, hosting visiting scholars, conservationists and students from a wide variety of academic disciplines.

The impact reaches well beyond archaeology. Recent projects range from monitoring jaguar populations, funded by the Disney Conservation Fund, to educational outreach in Maya schools.

“We’ve always called it a reserve without boundaries,” Bey said. “That’s what we want it to be.” The mission blends scientific discovery, cultural preservation and community engagement.

The goal is that the site may one day qualify as a UNESCO World Heritage destination.

Transforming the Student Experience

For Millsaps undergraduate students, the reserve offers something few other colleges can match: the chance to do field-based research in an international setting.

And you don’t have to be an anthropology major to benefit. Classes and field programs hosted on the reserve have centered on biology, business, mathematics, education, art and more.

And you don’t have to be an anthropology major to benefit. Classes and field programs hosted on the reserve have centered on biology, business, mathematics, education, art and more.

“I never assume a student will grow up to be an archaeologist,” Bey said. “I think if you can work in the jungle under really difficult conditions, collect good data and work with people from other cultures, those are skills you can take into whatever you do.”

That sentiment rings true for many Millsaps alumni who studied abroad in the Yucatán. One went on to lead a heart-transplant program at a major Manhattan hospital. Another told Bey the Yucatán experience helped prepare him for the rigor of law school. Unique experiences like this build confidence that fuels careers in science, medicine, public service, academia and the arts.

At the Cutting Edge

Millsaps’ use of lidar places it among a select group of institutions using the most advanced tools in Maya archaeology, particularly in Mexico. The findings are helping scholars rethink how Maya civilization developed and how ancient populations were distributed.

“We’ve jumped decades in a matter of a few years because of lidar,” Bey said.

That leap forward hasn’t gone unnoticed. A 2019 National Geographic documentary episode Lost World of the Maya shot on Millsaps’ Yucatán reserve has drawn over 30 million views.

A Vision for the Future

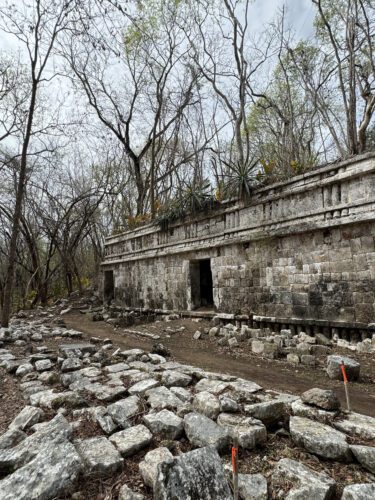

As the Millsaps Biocultural Reserve enters its next quarter century, its role extends far beyond excavating ancient ruins. It stands as a living classroom and a bridge between cultures.

As the Millsaps Biocultural Reserve enters its next quarter century, its role extends far beyond excavating ancient ruins. It stands as a living classroom and a bridge between cultures.

Bey sees that as central to the college’s mission. “The relationship we have with the Yucatán and our commitment to international education has embedded itself as part of our identity as a college,” he said.

To celebrate twenty-five years of active research, teaching and learning in the Yucatán, Millsaps has invited alumni and friends to visit the reserve this October. Guests will tour the tropical forest biocultural reserve, archaeological dig sites, classrooms, research facilities and the on-site library. There are many reasons Millsaps is ranked among the best in the country for study-abroad programs – and our Yucatán presence is one of them.

The long-term partnerships with local communities, Mexican scholars and conservation organizations ensures another incredible twenty-five years of collaborative, responsible global engagement for Millsaps students and faculty.

Instead of reading about breakthroughs, Millsaps students help make them, charting landscapes and uncovering stories no textbook could ever hold.